Reasons Why We Should Believe in Free Will Whether It Exists Or Not (Perspectives Part 4)

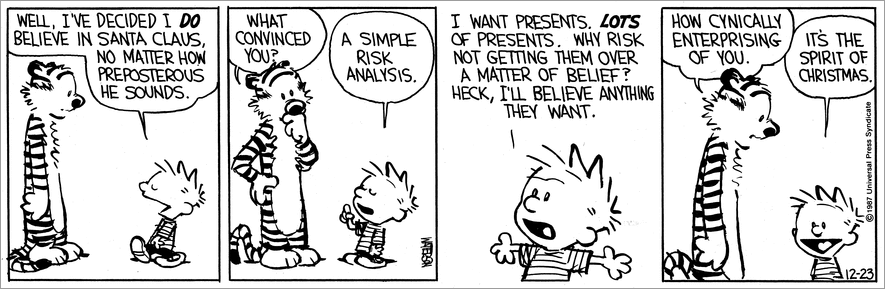

One of the assignments from the philosophy course I took this summer was to design a philosophical comic strip that outlined a key metaphysical concept of our choice. Now, I'm no Bill Watterson but between my limited comedy writing skills and my best friend's compensating artistic talent, this is what we were able to come up with.

|

Hopefully it goes without saying, but the philosophical concept I chose to comicize was determinism, which along with the concept of free will and the perhaps less-well-known theory of compatibalism, has drastic implications both on the future, as well as on each individual's present, daily lives.

You've probably heard of free will before— it's the theory that human beings have the ability to make their own conscious choices that have influence over the future. Free will permits us to act at our own discretion without the constraints of necessity or fate.

Determinism on the other hand, is the idea that all our choices are already predetermined, and that there is nothing anyone can do to change the past, present, or future. There are a couple different approaches to determinism, including causal determinism which theorizes that cause and effect relationships invariably lead from one to the other to determine the future, theological determinism which theorizes that a God determines the future, and biological determinism which concludes that the genetic programming of living creatures establishes everything they do, which consequently determines the future. Each of these methods differs from the others, but fundamentally, they all suggest an external influence, independent from human will, that has authority over human action and human thought.

And if you're having trouble coming to terms with the implications of free will or determinism, perhaps you'll be more inclined to adopt compatibilism, which in simplest terms, is a compromise between the two theories. A compatibilist would suggest that humans get a small amount of options in an essentially determined universe. If the universe was a road trip, compatibilism might allow you to choose the radio station and snacks for the drive, even though you have no say in the destination.

The Determinist Argument

Laplace's Demon, although it is thought-provoking, isn't backed up by any meaningful evidence beyond Laplace's assumptions. Since 1814 however, determinists have become more determined than ever to provide sufficient arguments.

The sufficiency of these arguments began to emerge about 150 years ago with the intellectual revolution that accompanied the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Because even though Darwin's work never explicitly states the implications that his theory of evolution has on free will and determinism, they were drawn out by his cousin, Sir Francis Galton. Galton concluded that if we have evolved, then mental faculties like intelligence must be hereditary. But we use those faculties to make decisions, so our ability to choose our fate is not free, but depends on our biological inheritance.

More recently, neuroscience research on the inner workings of the brain has conducted further investigation to Galton's theory. Modern brain scanners now allow us to look inside a living person's skull, revealing intricate networks of neurons that determine our thoughts, hopes, and memories. Thanks to this technology, neuroscientists have reached a general consensus that these networks are shaped both by genes and environment. And American psychologist Benjamin Libet took this discovery one step further in the 1980's when he proved that the electrical activity that builds up in a person's brain before they, say, move their arm, occurs before the person even makes the conscious decision to move.

If these arguments are too technical, many determinists consider how changes to brain chemistry can alter behaviour. Between alcohol and antipsychotics— not to mention the way fully-matured adults can become murderers or pedophiles after developing tumors in their brains— human decisions can clearly be effected by chemical balances in the brain, and thus many argue that humans are dependent on the physical properties of their grey matter and nothing more.

The Free Will Argument

A lot of free will adherents would call on German philosopher Immanuel Kant's arguments against determinism, which touch on a concept that the Christian tradition would label our "moral liberty." Essentially, humans have an undeniable innate obligation to chose between right over wrong, which is made apparent through the inherent guilt we feel when we neglect that duty, and as Kant put it, "if we are not free to choose, then it would make no sense to say we ought to choose the path of righteousness." Of course, some would suggest that we don't ought to choose the path of righteousness, but this counterargument is simply ignorant to the structures our society is based on. Incarceration systems, the Nobel Peace Prize, and everything in between is more or less established on a universal accountability for doing the right thing.

But moral liberty aside, one of the biggest problems I have with determinism is that it contains a logical fallacy. The fact that a determinist would even attempt to convince others of their position shows that they rely on the free will and volition of the people they are trying to convince. The theory of determinism implies that everything, including an individual's thoughts and beliefs, are determined by some kind of preexisting cause, which means it would be impossible to change another person's stance.

* * * * *

As you're probably discovering, free will and determinism are far more complex and far less fathomable than they're often credited as. But whether you're compelled by the implications of the free will argument, convinced by the assertions of the determinist argument, or merely disoriented and confused by it all, assumptions of free will run through every aspect of our lives. From politics, welfare provisions and incarceration to world sports championships and Academy Awards, a general acceptance of free will is the foundation for a functioning society. I mean, can we really justify imprisoning criminals for crimes they had no choice but to commit? And are anyone's accomplishments truly deserving of praise if they were simply predetermined? Even the century-old American dream— the belief that anyone can make something of themselves regardless of their start in life— is entirely based on the ideals of conscious, intentional choice.

The importance of free will also transcends society's constructs, and appertains to individual moral conduct. A 2002 study was conducted by psychologist Kathleen Vohs and Jonathon Schooler, in which one group of participants was asked to read a passage arguing that free will was false, and another group was given a passage that was neutral on the topic of free will. Each group was then asked to perform a number of tasks (eg. take a math test in which cheating was made easy, or hand in an unsealed envelope full of loose change), and the participants who were conditioned to deny free will were proven more likely to behave immorally.

There is advantage to regarding free will as real, not because it is necessarily true (although I believe it is), but because, in the words of Barack Obama, "values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will."

And that's why we should believe in free will whether it exists or not.